Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

Every morning, Sean Yates gets up early to fill up water bottles. It’s a daily ritual that’s been part of his life since he emerged as one of Britain’s pioneering riders a generation ago. But these days, he’s not topping up bidons. It’s 30-liter plastic jugs.

Yates is still riding his bike every day, but his morning routine is radically different since he moved to a remote farm near Spain’s central Mediterranean coast a few years ago. Yates decided to unplug to fulfill a long-held dream of living a simpler, closer-to-nature lifestyle. How simple is it? Yates now lives without the luxuries of running water or electricity.

“We are living off the grid,” Yates told VeloNews. “It’s on about 10 acres, at the end of 5km on a dirt track.”

Yates, along with his partner and a six-year-old son, now leads a very different lifestyle after turning the page on the itinerant lifestyle of a bike racer and sport director. Instead of mapping out a racing strategy, he’s working in the garden, doing morning chores, and just lounging around in the inviting Spanish sun.

Yates, whose career arc includes 15 years in the elite peloton and 15 more as a sport director for some of the peloton’s top teams, decided to unplug and chill out after a lifetime of chasing wheels.

“We’re really out there,” Yates said. “I go down to the local spring to fill up on drinking water. It’s a very different lifestyle than going to the race, that’s for sure.”

Yates probably wouldn’t have even known there was a worldwide pandemic if it wasn’t for his cellular phone.

Social distancing is now something that comes naturally. Yates’s farm is inland, about 18 miles from the bustling seaside resort beaches Benicàssim, and about five miles to the nearest village at Useras.

Far from the rolling circus

When VeloNews spoke to Yates earlier this spring, Spain was in full lockdown mode due to the coronavirus pandemic. For Yates, however, life on the farm is pretty constant. His son was at home, instead of at the local school, and Yates couldn’t ride his bike for several weeks, but otherwise, life off the grid hadn’t change that much, even during a world health emergency.

Surrounded by almond and lemon trees, Yates keeps busy attending to the family’s sprawling compound. There are solar panels, a compost pile, and rainwater collectors to fill 1,000-liter tanks. With plans to build a home still ongoing, they’re living in a 20-foot trailer and an old van right now. They tap electricity off the solar panels, enough to charge his smartphone and pick up a signal to work his coaching business.

“We don’t just sit here twiddling our thumbs,” he said. “When you’re living off-grid, there’s a lot of work to do every day.”

Yates, who turned 60 in May, also runs a private coaching business, working with a dozen or so top British amateurs, using his cell phone and laptop to tap into the web — his only real connection to the grid these days.

Things were getting too crowded on the roads in southwest England for Yates’s liking, and he always wanted to live on the European continent. Yates liked southern Spain’s sun-baked hills and lush valleys after passing through the region during editions of the Vuelta a España, and started searching for some land. They found an abandoned farm with nice exposure to the sun and some terrain for a garden. Close enough to the beaches, but far from the tourist hordes, it was a perfect match.

“We just wanted to duck out and give it a go,” he said. “We liked the relaxed style of Spain. As long as I can ride my bike and take it easy, I’m happy.”

Since moving to Spain, he still rides almost daily, exploring the local hills, villages, and beaches. Occasionally, he’ll be spotted on the side of the road when a local race comes nearby. The Más de la Costa climb, used in the Vuelta a España, is not far, and the Volta a la Comunidad Valenciana rolls by in February.

They had some goats, but they were soon eating up all the vegetables that Yates was growing in a mix of garden beds. A few dogs, and some chickens run around the place to keep them company.

“We’re making it up as we go along,” Yates said. “We have views of the coast here. We were in T-shirts and shorts on Christmas day. It’s paradise.”

Yates also wanted to slow down the wheel after a long career on the road. With a palmares that included a stage win in the Tour de France as well as a day in the yellow jersey, and a sport director career that saw him behind the wheel in Bradley Wiggins’ historical Tour victory in 2012, Yates had seen it all.

His move to his Spanish idyll, however, almost didn’t happen.

The fall that nearly took his life

At the end of 2016, Yates suffered what he described as a “bad accident” in a horrific fall from a tree when he literally impaled himself on a branch.

For years during every off-season, Yates ran a local gardening business, including trimming the hedges of his neighbors back home in southeast England. Yates started doing it early in his racing career to earn a little cash during the winter break, and kept it up after retiring from racing.

“Since I retired, I’d been cutting hedges as a hobby for a few local clients in Sussex area,” he said. “It kept me busy over winter, and I had some clients for more than 20 years.”

In the winter of 2016, Yates was at the top of a ladder with a chainsaw clearing out some branches when he tumbled — he estimates the fall of about three meters — and landed directly onto a sharpened branch. The limb literally impaled him, driving up through his loins and into his lower digestive tract.

“That almost did me in,” Yates said matter-of-factly. “A branch went right through me. I was quite lucky I survived, to be honest.”

The nearest hospital was eight miles away, and after the adrenaline had worn off from the fall, Yates – still in his work clothes covered in wood chips and dirt — realized he would have to go to another hospital in Brighton, even further away. Because of the delicate nature of the injury, doctors were worried that the branch might have punctured one of his intestines or part of his digestive tract, which could lead to internal bleeding and life-threatening infections.

“I was in a real state when they wheeled me in,” he said. “It was a stupid mistake. I fell about 10 feet onto a big hedge, and a branch went straight into me, right next to my anus. I kept falling, and an eight-centimeter piece was left inside me.”

Doctors found the broken piece of branch lodged inside Yates, and he underwent a delicate six-hour operation. Yates was bed-ridden for six weeks with a fractured sacrum bone, and an injured calf muscle that still gives him trouble. Luckily, there were no major internal injuries, and after about a year of recovery, he was able to make the move to Spain.

“I am fully recovered,” said Yates, who now has a big scar in front of his stomach. “It’s amazing what they can do these days.”

Yates, who never made the big-money contracts during his racing days, found an unexpected benefactor to help pay for the mounting hospital bills — Bradley Wiggins.

The 2012 Tour de France champion is an avid collector of bike memorabilia, and when Wiggins heard that his ex-sport director was in trouble, he came to help. Wiggins ended up buying Yates’ yellow jersey he held during the 1994 Tour de France after riding into a breakaway in stage 6.

“The money from that sale of the jersey enabled me to have that operation,” Yates said. “As fate would have it, what goes around, comes around.”

The accident came on top of other health issues for Yates, who has suffered from heart problems during the past several years.

“My heart is not functioning that great,” Yates said. “I’m really limited in going uphill, which is frustrating. I’ve had plenty of time to ride my bike in my past, and I feel good when I am riding it, except when I try to follow someone on a climb. I am keeping my shape, and I’m still quite strong. On the flats, I can still motor along.”

Yates, who used to ride long transfers on his bike between stages when he was working DS at the Giro or Vuelta, is now an ambassador for bike brand Ribble, which helps takes the edge off the steeper climbs. The recent health issues only make Yates more appreciative of his rambling Spanish compound.

“I’m as good as I can be,” Yates said. “I lived to tell the tale, as they say.”

Full circle in legendary career

Yates’s move to Spain is the latest chapter in his extraordinary career. Most of today’s younger fans might recognize Yates from his sport director gigs at Sky, Tinkoff-Saxo, or as one of the founders of the ill-fated Linda McCartney team.

Yet back in his day, Yates was one of the pioneers of European racing in the 1980s and 1990s. He was part of the “Foreign Legion,” a generation of riders who barnstormed the traditional European strongholds and marked the internationalization of the peloton long dominated by French, Italian, Spanish, Dutch, and Belgian riders. Yates raced alongside such figures as Greg LeMond, Steven Bauer, Allan Peiper, Paul Sherwen, Robert Millar, Phil Anderson, Stephen Roche, and Sean Kelly who were among a generation of Anglo racers who reshaped the European peloton.

Yates raced against some of the greats during his career, but for him, Bernard Hinault is tops.

“The boss during my time was Hinault,” Yates said. “Eddy [Merckx] is untouchable as the greatest of all time, but second was Hinault. The way he bossed things, his strength, his constitution, he was just insane.”

Yates was so in awe of Hinault he rarely spoke to the French star. One time he bumped into Hinault as the pack roared in for a sprint at the Tour. Yates, who was sporting the new wide-frame Oakley sunglasses of the time, said Hinault gave him an ear-full.

“I never saw him much in the race, because he was always right at the front and I usually floated around at the back,” Yates said. “I bumped into him once during the 1985 Tour, and he said to me, ‘Take off those damn sunglasses and maybe you can see where you’re going!’”

Yates said Hinault was the last true “patron” of the pack, saying the tradition, like many of the other old-school practices, has died off in the modern peloton.

“Hinault was an absolute beast. He would absolutely crush people mentally and physically,” he said. “He always rode at the front of the bunch, either to tell everyone to go slow, or to make it miserable for everyone if he wanted to go hard. He was a mean motherfucker who had the legs to back it up.”

In many ways, Yates’s career followed the evolution of the traditional European-dominated peloton, from the arrival of international stars like LeMond, to today’s science and technology-driven peloton and million-dollar contracts. Yates said his first contract was for about $700 a month, which was better than he’d earn trimming hedges in Sussex. Today’s top stars are pulling in seven figures.

“Greg elevated things to the next level,” Yates said. “Cycling was different in those days. Back in the day, it was much more fun. You could chat with your mates. There was not this constant pressure, it was much more relaxed, and [to] ride along all day, then have a sprint, then you’d go off to the hotel. There was more pressure on the winners to be at the front, but in general, it was a lot more fun. Of course, there were not the financial rewards, either.

“Today there is no let-up,” Yates said. “I don’t envy guys racing today. Teams are a lot more serious today. Guys like [Bjarne] Riis or Sky, they have a plan for every race. It’s a lot more cutthroat now. Nothing is free in cycling.”

In fact, Yates never really expected to become a professional cyclist, but his passion has always been about the bike. In the mid-1970s, Yates started to race on what was once the very busy English time trial racing calendar. He didn’t have much coaching in his early days, but he made up for it in brute strength. By the late 1970s, he was one of the top time trialists, eventually beating his childhood idols, and earning himself a ticket to the 1980 Olympics in Moscow.

“I was a rider who always took things one step at a time,” Yates said. “I never thought about where I wanted to go. I never dreamed of becoming a pro.”

His results landed him a gig at the legendary French amateur team, ACBB, in 1981, which led to a pro contract with Peugeot in 1982. The doors to Europe were opened, and soon earned the nickname “The Animal” for his pure strength, time trialing prowess, and descending skills.

“I struggled initially, because I didn’t come from a cycling background,” he said. “I didn’t have that entrenched into me about how you’re supposed to look after yourself, stay skinny, and it held me back until I got to grips with it through my errors.”

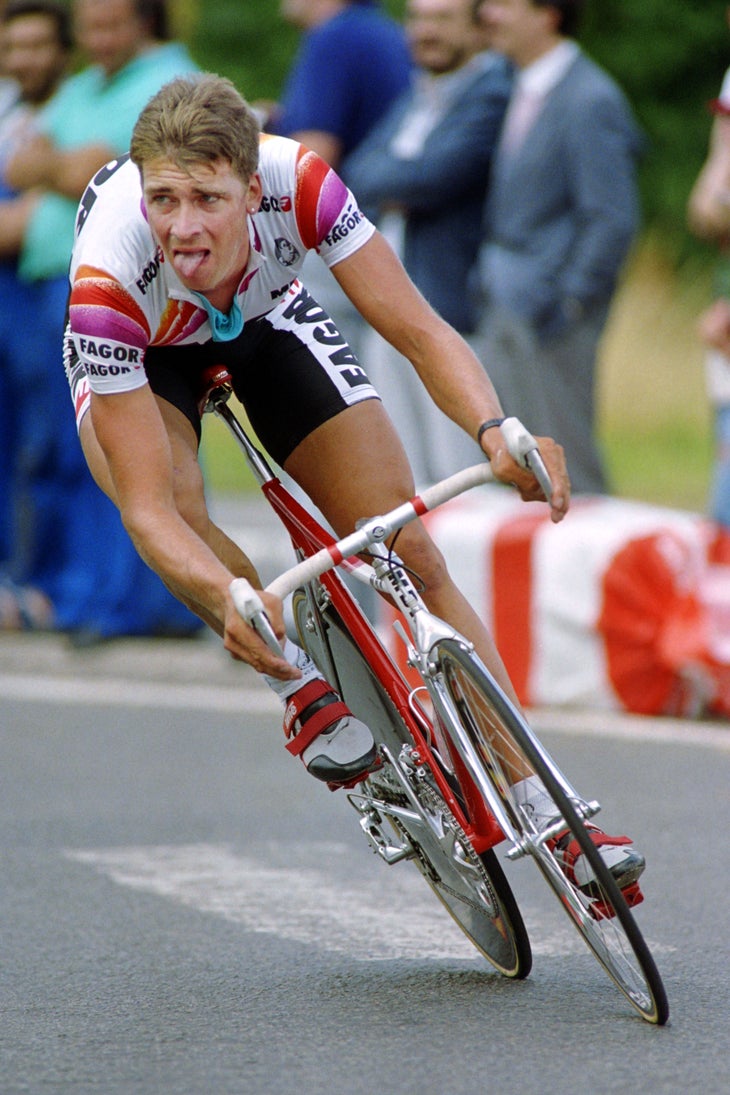

Yates went on to ride for Fagor, 7-Eleven and Motorola, winning stages at the Tour and Vuelta as well as the national road title, before retiring at the end of 1996.

Though he’s off the grid these days, cycling is never far from his life.

Yates was back in the headlines last month with news he would be joining Nippo Delko One Provence as a coach, marking his return to pro racing since leaving Tinkoff-Saxo as DS at the end of 2016.

“I have spent my whole life on the road, so to suddenly to be settled down into tranquil is quite a change,” he said. “I never have actively searched out employment, it always comes to me.

“I follow cycling as closely as I ever had,” Yates said. “Cycling [has been] in my blood since I was 17. It’s what keeps me ticking.”

Yates says he stays in touch with close friends in the peloton, such as Wiggins, and Trek-Segafredo sport director Stephen De Jongh. He was crushed by the passing of Ineos sport director Nicolas Portal, who died in March, at 40. In fact, Portal was planning a trip to visit Yates at his farm.

Yates considers himself one of the few lucky people in the world who can do professionally what they’re most passionate about.

In fact, if he had the chance to do it all over again, he wouldn’t change a thing. Yates imagines himself as a super-domestique, riding alongside Luke Rowe at Team Ineos.

“I would want to be a rider again,” Yates said. “That’s what I was born to do — to ride a bike.”